By: Tara Elsa

“There is no joy more intense than that of coming upon a fact that cannot be understood in terms of currently accepted ideas.” -Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin

While today we recognize women astronomers for their contributions, in the past, their accolades went unrecognized. From discovering comets to advancing education for women in STEM, women astronomers overcame many obstacles for hundreds of years.

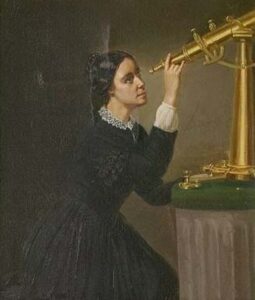

MARIA MITCHELL (1818-1889)

One of the most famous female astronomers is Maria Mitchell, known for being the first American scientist to discover a comet in 1847 at the age of 29. Mitchell was born to Quaker parents who taught her that boys and girls should both be educated. Inspired by her father’s interest in space, Mitchell began learning about astronomy, mathematics, and navigation. By 14-years-old, she rated ships’ chronometers for long whaling journeys.

Mitchell took on many astronomical feats in America. At a young age, she became the first librarian at Nantucket Atheneum in Massachusetts because of her love for learning. At just 16-years-old, she completed her education and opened a school for girls to learn STEM. This set her career in astronomy in motion.

One day in 1847, Mitchell spotted a small, blurry object in the sky that didn’t appear on her charts; it turned out that she discovered a comet, making her the first American scientist to discover one!

Within the next several decades, she became America’s first woman astronomy professor and first professional woman astronomer. As a lifelong advocate for women in STEM, she continued her support when she became the founder of the Association for the Advancement of Women and one of the first women to work for the US federal government. Because of her accomplishments, Mitchell received a gold medal from the King of Denmark—making her the first American to receive this award—and the comet she discovered became known as “Miss Mitchell’s Comet.”

CAROLINE HERSCHEL (1750-1848)

Caroline Herschel was one of the most influential women astronomers, breaking gender norms for her time. Born in 1750 in Hanover, Germany, Herschel lived with her mother and her father, who was a talented musician. At age 10, Herschel got typhus which permanently stunted her growth. Told by her parents that she wouldn’t marry and should instead be a house servant to the family, she left to live with her brother, William, in Bath, England.

Despite the gender norms present at the time that often prevented women from obtaining careers in STEM, Herschel worked alongside William and discovered three new nebulae in 1783. Nebulae are giant clouds of dust and gas in space, formed by either the formation of new stars or through the explosion of a dying star. Herschel didn’t stop there.

Beginning her 11-year series of discoveries in 1786, she became the first woman in the world to discover a comet. In the following years, she discovered seven more comets and documented all of the work of her and William over the years. Some of the published catalogs are still being used today!

Herschel pursued other interests, many of which were inspired by her brother. She began singing lessons from her brother and eventually became a professional singer. When her brother began pursuing his passion for manufacturing telescopes, Herschel stepped in to aid in manufacturing more powerful telescopes. Alongside her brother, she also developed a new mathematical approach to astronomy that’s still used to this day. Because of Caroline Herschel’s groundbreaking discoveries and bravery, she was awarded the King of Prussia’s Gold Medal of Science in 1846 at the age of 96.

CECILIA PAYNE GAPOSCHKIN (1900-1979)

Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin was an influential woman in astronomy at a time when there was a lot of change for women in America. She’s most known for her high academics and stellar discoveries. Gaposchkin was born in Wendover, England in 1900. In her early collegiate studies at Cambridge University, a professor invited her to use the Cambridge Observatory’s collection of astronomical journals, and she discovered her love for physics.

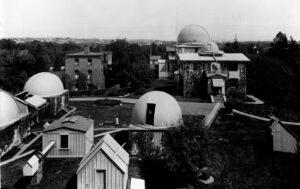

She saw little room for advancement for women in the field and moved to the United States where she was offered a graduate fellowship at the Harvard College Observatory. This aided Gaposchkin’s studies as Harvard had the best global collection of stellar spectra on photographic plates at the time.

In her college thesis in 1925, Gaposchkin took what she learned from Harvard’s best astronomical research and discovered a way to determine the composition of stars. By learning a way to measure the absorption lines in stellar spectra, she could determine the makeup of the stars along with their surface temperatures. Through this research, she also discovered that the Sun and other stars are primarily composed of hydrogen and helium. Since Harvard didn’t grant doctoral degrees to women at the time, Gaposchkin received her degree from Radcliffe College, making her the first woman to be awarded a PhD in astronomy.

Following her graduation, she turned her thesis into a book, Stellar Atmospheres. For her work in astronomy, she was awarded the prestigious Henry Norris Russell Prize by the American Astronomical Society in 1976.

INSPIRING FUTURE WOMEN IN STEM

These are just some of many significant women astronomers who have advanced STEM education for women and discovered new stellar phenomena. By celebrating their accomplishments and discoveries, young women will be inspired and encouraged to pursue careers in STEM.

To encourage youth in your life to enter into STEM-based careers, be sure to visit our Aviation & Space Museum! We’re open daily and offer educational experiences for all age groups. Buy your tickets today!